Over the past several months, this blog has rightly focused on high speed passenger service, because that will be the primary task of the California network. This post will discuss the other potential application, that of high speed cargo. This would be suitable for a range of light high-value time-sensitive goods, e.g.

- mail and packages

- pallets of high-tech manufacturing parts

- critical spare parts for machinery

- meat, poultry and fish (in suitable auto-refrigeration units)

- eggs, packaged dairy and farm-fresh produce (well insulated)

- fresh cut flowers (idem)

- general air cargo in standard unit load devices (ULD)

On page 13 of Chapter 1 of its 2008 business plan, CHSRA indicates it is at least aware of the possibilities:

"While the high-speed train system is not compatible with typical U.S. freight equipment and operations, the proposed high-speed train system could be used to carry small packages, letters, or any other freight that would not exceed typical passenger loads. This service could be provided either in specialized freight cars on passenger trains or on dedicated freight trains. Moving medium-weight high-value, time-sensitive goods (such as electronic equipment or perishable items) on the high-speed train tracks would also be a possibility but would need to be operated overnight when it wouldn't interfere with passenger operations and would require additional facilities for loading and unloading."

Note that this is essentially a technical assessment. The business case for running such a service in California would need to be made by a freight operator, which could be either a new company or an autonomous new division of an existing one.

There is already one precedent: in France, state-owned La Poste has long operated a small number of yellow cargo TGV trainsets at speeds up to 250km/h (~150mph) on the core Sud-Est line between Paris and Marseille in lieu of domestic air mail.

Video of La Poste TGV

There are now plans to take this one step further by forming a joint venture between SNCF Fret - the company's rail freight division - and La Poste called Fret GV (fret a grande vitesse = high speed freight). The primary business for this new JV will be mail and parcel service plus possibly light pallets. The rolling stock will be converted first-generation TGVs that SNCF is gradually replacing with newer, faster models.

A competing consortium called Carex (CARgo EXpress) is gearing up to provide connecting ground service for selected ULD sizes between airports on the Thalys network (northern France, Benelux, Cologne) and through the Channel Tunnel to London. Future extensions are planned to Spain and Italy as well as to Berlin, though Deutsche Bahn's HSR network is patchy. The driving forces behind the trans-national Carex effort appear to be the operators of Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris and, Liege Airport in Belgium. The service, which is not yet in operation, will likely be based on 20 trains featuring custom derivatives of Alstom's TGV Duplex design, as single-level concepts cannot accommodate the height of standard ULDs.

FedEx and UPS are both studying the opportunity, which promises to deliver more reliable delivery times than Europe's congested roads. Moreover, many airports do not permit nighttime operations, but HSR can operate 24/7 - especially at night, albeit with some speed restrictions in built-up areas to keep the noise down. For additional details, please see this PDF.

Meanwhile, DHL may decide to use a new high-speed rail line under construction for a rail freight forwarding service between Frankfurt/Main and its new European hub at Leipzig/Halle airport.

All of these examples are completely different from traditional rail freight, especially the cost-sensitive long-distance heavy container freight so dominant in North America. High speed cargo operators need to position themselves not against ocean or inland shipping but rather, in-between air cargo and medium-distance trucking. This niche requires fast, efficient transshipment from aircraft to trains to trucks/vans (and vice versa). In particular, sidings located directly on the premises of airports that can operate at night confer a real competitive advantage. In the California system, that would mean Ontario, Palmdale and possibly, Castle airport in Merced County.

Dedicated high-speed lines usually impose a load limit of 17 metric tons per axle. Heavier trains would cause excessive wear and tear on the rails and excessive geometry creep on the trackbed, especially in high speed curves. Lowering speeds through those curves reduce the dynamic loading, but below a certain point the flanges of the inside wheels will press too hard against the inside of the rail, again causing excessive wear and a lot of noise besides. This is a function of the amount of unbalanced superelevation permissible for the line - the bank angle can only compensate centrifugal forces exactly at one speed, the design target velocity. Gradients are another important factor for high speed cargo: consists must be able to climb and descend 3.5% inclines at fairly high speeds. In practice, that means short trains and plenty of traction power. However, older tractor-based designs are preferable to modern EMUs in this case - you want to use the permissible axle load on the cars for payload, not electric motors.

During the day, only the lightest of cargo - i.e. mail and packages - can be transported at the very high speeds required to keep pace with passenger traffic. Labor costs can be reduced and line headways maintained by attaching "hitchhiker" cargo trainsets to regularly scheduled passenger trains. Coupling and uncoupling at a passenger station is very quick, but a driver for the cargo trainset would have to be present to support the procedure. Note that European and Japanese coupler designs are incompatible with one another, FRA might have have to choose one or the other for high speed trains in the US.

Video of two ICE3 trains coupling

Alternatively, single high-speed passenger trainsets operating at the "local" or "semi-local" service levels could be scheduled to also stop at dedicated high speed cargo yards with run-through tracks, These could be many miles from the nearest passenger station but would still be integral to the high-speed network and therefore, topologically separate from traditional freight railyards where passenger trains are prohibited. In practice, the passenger train would drop off its current cargo trainset, if any, then (optionally) proceed a short distance down the track so a new one can be coupled and its temporary driver alight. The sidings in the high-speed cargo yard would feature wide platforms so multiple forklift trucks could quickly unload and re-load the trainset that was just dropped off so it can hitch a ride on another passenger train scheduled later in the day. The delivered cargo would immediately be moved to a waiting aircraft, truck or sorting facility, as appropriate. Note that a ULD might be used for a particular shipment even if it never leaves the ground, simply because that's what this logistics system would be designed around.

At night, when there would be at most a few sleeper passenger trains on the network, high speed cargo trains could operate autonomously in single or double trainset consists. Obviously, the operator would have to employ drivers for the graveyard shift. This is non-trivial, even with PTC safeguards, as humans tend to make more mistakes in the small hours of the morning. The biggest technical obstacles to leveraging the expensive high-speed infrastructure 24/7, other than finding suitable locations for the yards, is minimizing rail-wheel noise when passing through built-up areas at moderate speeds. Spanish manufacturer Talgo and Kawasaki/Hitachi in Japan are arguably leaders in this field.

The CHSRA quote also suggests that medium-weight goods could potentially be transported on the high speed network. For reference, there are several traditional systems of intermodal truck-on-rail transport:

- "rolling highways", essentially rail ferries (e.g. Alps, Channel Tunnel)

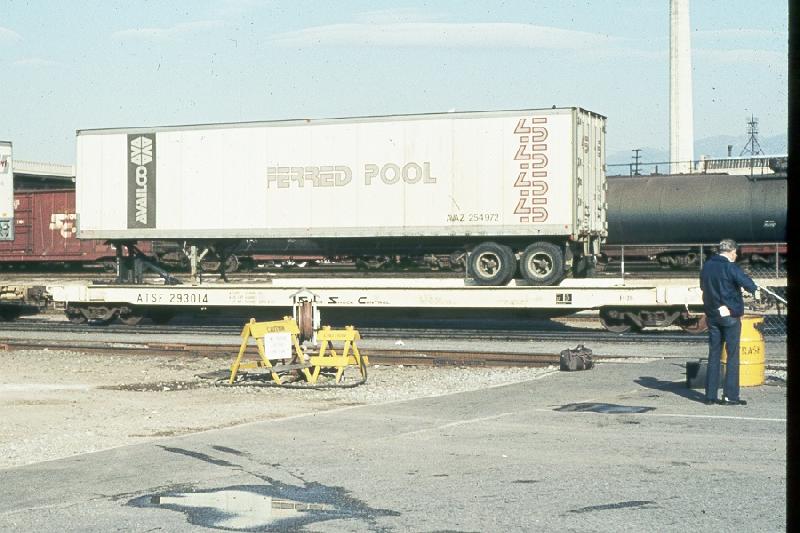

- trailer on flatcar (TOFC), allows tractor units to remain local

- TCSC ad-hoc rail cars, an ingenious but complex system used east of the Rockies

All of these have one big disadvantage: consists must either be assembled using yard shifter locomotives or, trains must be loaded and unloaded at one or both ends. This takes a long time, sharply reducing the advantage of combining local trucking with electric rail over diesel-guzzling long-distance trucking. A modern take on TOFC that greatly improves trailer transshipment is the Modalohr system. In Europe, it operates on regular lines, but that would not be permitted in the US - the special flatbed cars are currently not designed to FRA standards. Note that the mechanisms for turning the trailer trays are embedded in the transshipment terminals. If required, an entire train can be unloaded and re-loaded in less than 30 minutes.

Video of the Modalohr TOFC system

This is an excellent example of what I would call rapid freight, as opposed to both conventional heavy freight and high speed cargo. Thanks to horizontal loading, the system is compatible with regular height overhead catenaries. In California, the challenge would be to keep the axle loads under 17 metric tons to avoid damage to the expensive high-speed line, since FRA won't permit mixed traffic on legacy freight tracks. Perhaps a push-pull combination of locomotives might be possible. If so, a large number of trucks could be taken off highways in the East Bay, the Central Valley and in the LA basin, all areas where air quality and congestion are especially problematic.

8 comments:

Note that the California HSR system would be contained within the state of California, and well less than the full length of the state, so this freight would be competing with short and medium distance trucking rather than competing with long distance trucking.

For short and medium distance freight, European rail operators occasionally use a Cargo Sprinter type train. An electric version, with a generator trailer for operating in a marshaling yard, would substantially reduce marshaling delays per consist.

I think it is great to allow light cargo on the system, even during the regular span of hours for passengers service.... so long as passenger service is not affected.

But, I am of the opinion that the statement made by the CHSRA will need to be revisited. Specifically, the applicability of running trains during non passenger service hours.

If BART is an applicable example, they do not run trains 24/7 because they need a reliable window of time for maintenance in the ROW. That time is during the middle of the night.

BART systemis large, but the CHSRA system would be much larger. Certainly some track maintence, even inspection, needs to occur on a regular weekly and nightly basis.

I suspect the CHSRA making that statment was to appease interests, whereever or whome ever they were, that cargo was a possibility and mute or tone down their opposition for the time being.

@ BruceMcF -

California is a large state with a large population. It's probably a viable market for high speed cargo and rapid freight in its own right. Long-distance interstate rail freight will always be important because of the ports, but there may be plenty of in-state business opportunities if speed and flexibility are improved.

The CargoSprinter is another good example, through it relies on a modern rail network that can handle axle loads higher than 17 tons at intermediate speeds. That means track with some superelevation, geometry databases, PTC infrastructure etc.

Wear and tear of the rails and trackbed is proportional to the fourth power of axle load, same as for roads. One locomotive with four axles at 22 tons each will do as much damage as 3 cars that stay under the limit for high-speed lines. Running even medium freight will drastically increase infrastructure maintenance costs, rendering high-speed passenger service that relies on speeds of up to 220mph unprofitable. There's a reason most of the European network is rated at or below 200km/h (125mph) and, it's not just because of curve radii.

The US has spent the last 50 years disinvesting in its rail infrastructure and it shows. In the near term, I doubt the CargoSprinter concept would be technically feasible in California, even if someone could make a business case for it.

@ Brandon -

BART doesn't need to do track maintenance every night. For inspection of the state of good repair of the track and catenary infrastructure, the Japanese use a small fleet of special test trains called Dr. Yellow.

If CHSRA decides it wants to allow operators to run some trains at night, that doesn't mean they'll be allowed to run all night, every night. There will be scheduled maintenance blackouts, just as there are for every other 24/7 system (e.g. data centers).

The main sticking point for exploiting the infrastructure at night isn't maintenance, it's noise.

@ Rafael ... just noting the distinctive market segments being talked about here ... even Sacramento / San Diego would not normally be considered long haul trucking. That'd be more approaching 1,000 miles and up.

On the CargoSprinter mode ... to be more explicit, with a phrase like "an electric version of the CargoSprinter concept", the concept I referred to is the short consist, push-me-pull-me single stack container train, with automatic couplers for running in longer trains that can be quickly assembled and disassembled.

Lower axle loadings would require setting an appropriate maximum gross weight per container. Since shipping charges in these market segments tend to be set by the weight-mile, the system is already in place in most warehouse operations to monitor weight loaded per container. If the CAHSR system is to be used for freight, monitoring of axle loads at freight access points would be needed in any event.

And if there is an electric bus in the auto-coupler, then attaching a generator trailor to take a consist out from under the wires would be a straightforward operation.

I think a distinction should be made between cargo and freight. Freight is much heavier compared to cargo, correct?

Because of the loads expected with freight, freight does not seem compatible at all on the HSR network; too slow and affects infrastructure too much... affecting tolerances needed for HSR.

No one needs a bumpy ride at 220mph!

Lighter cargo, on the other hand, appears much more compatible.... assuming the conveyance does not affect scheduled passenger services.

Rafael-

Good work furthering thought on inspection and maintenance and compatibility with non-passenger services. I am not sold yet on the solution, but I am not a decision maker with the CHSRA either!

I look forward to additional coverage on this as the system progresses and policies get vetted... likely learned about in the media, but here too.

Hypothetically speaking, if fulltime staff/labor committed to inspection and mainteance are not needed for the network ROW... I can see that work occuring by contract to a 3rd party. And, the staff/labor of that 3rd party could maximize their own effeciency by working on track networks of other systems while not needed on CHSRA.

In fact, UPRR or BNSF may be contracted to maintain CHSRA ROW. Or vice versa.

The possibility of these options seems more possible with maintenance staff being based at regional locations than a single centralized place.

Cargo is goods carried by a large vehicle ... truck, train, ship, barge, airplane. So is freight.

Freight comes in heavy or bulk freight, medium freight, and light freight. Light freight is certainly compatible with the limit on axle loadings for a freight car on the HSR network, heavy freight is certainly incompatible, and there would be a dividing line somewhere with medium freight. The heavier the weight overheads per axle, the lower the ceiling would be on the tare weight.

Isn't a standard 40' container already limited to 30 tons, so that with two axles to a container it'd be under 17 tons/axle?

@ Brandon -

UPRR and BNSF have zero expertise in maintaining high speed lines. However, it's quite possible that infrastructure maintenance will be outsourced via a long-term maintenance contract to (California subsidiary of) the specialized vendor whose technology is chosen for the construction of the line. Something similar may apply for trainset maintenance.

@ Alon Levy -

you have to count the weight of the flatbed car incl. the trucks as well, not just the payload. Such cars usually have four axles, so with a single container the whole thing might be under the limit. The locomotive probably wouldn't be.

As BruceMcF indicated, running a moderate number of medium freight trains is a grey area. In Europe, it wouldn't even be considered because the rest of the network can handle that application. I picked TOFC as an example because it is better suited to rapid horizontal transshipment. Shipping containers have to be lifted with a crane.

Post a Comment