by Rafael

Conventional wisdom has it that HSR in California equals long-distance trains from Northern to Southern California. However, just because trains can cross mountains doesn't mean that passengers will always want to. More often than not, their origin and destination will lie in the same region, i.e. Bay Area, Central Valley or Southern California. Over time, HSR may change that, but it would be prudent to study service models that accommodate a combination of intra-regional and inter-regional trains on the same timetable.

Keep in mind that CHSRA is not a railroad, it is only responsible for planning and constructing the HSR infrastructure. That will be owned by a separate, yet-to-be-created entity in which the various investors, including the state of California, will have equity stakes. This entity will also fund any extensions. If European trends are any indication, a long-term (e.g. 20 year) contract for day-to-day operations and maintenance of the infrastructure will be awarded via open tender. Train operations governed by a timetable defined by the infrastructure operator may or may not be delivered by separate companies that bid for slots at regular auctions, e.g. every 4 years. Note that CHSRA has yet to announce the gory details of all this, so the above is just my personal educated guess.

NS HiSpeed A useful example from overseas is NS HiSpeed, a relatively new joint venture between the Dutch national railways (NS, 90%) and KLM (10%). On the one hand, this is an umbrella brand and online portal for all high speed trains to and from destinations in Holland, including those that cross borders. On the other, in terms of passenger volume, the most important segments of the HiSpeed network will likely be Amsterdam-Schiphol Airport-the Hague-Rotterdam-Breda, to be served by AnsaldoBreda V250 trainsets.

A useful example from overseas is NS HiSpeed, a relatively new joint venture between the Dutch national railways (NS, 90%) and KLM (10%). On the one hand, this is an umbrella brand and online portal for all high speed trains to and from destinations in Holland, including those that cross borders. On the other, in terms of passenger volume, the most important segments of the HiSpeed network will likely be Amsterdam-Schiphol Airport-the Hague-Rotterdam-Breda, to be served by AnsaldoBreda V250 trainsets.

In part because of teething troubles with ETCS level 2, this Italian manufacturer is late in delivering the equipment to NS HiSpeed and SNCB, the Belgian national railways who will deploy them on the Brussels-Antwerp-Rotterdam-Amsterdam route. In addition, the faster but also more expensive Thalys service featuring WiFi on board will remain operational. This somewhat confusing proliferation is a result of the planned liberalization for cross-border rail traffic in the EU in 2010.

This eye candy promo video features text in Dutch, but should be self-explanatory:

A key objective of the expensive HSL Zuid high speed line and the new NS HiSpeed services on it is to decongest the extremely busy motorways linking the dense randstad conurbation, home to about 10 million people. Most Dutch motorways have just four lanes total, though some have been widened to six.

The Dutch railways have long offered deeply discounted traintaxi service at 36 stations throughout the country, provided only that you buy the requisite coupon together with the train ticket. The service operates as a jitney, conceptually similar to airport shuttles in California but typically based on smaller vehicles. The driver selects the route ad hoc, rather than plying a fixed route (cp. dolmush in Turkey).

Caltrain HiSpeed? The construction of dedicated HSR tracks in the SF peninsula will mean the end of Caltrain's existing "baby bullet" service. However, electrification plus an expected FRA waiver to operate lightweight non-compliant EMU equipment plus a top speed of up to 90mph means that future Caltrain locals will have the same SF-San Jose line haul time (p2) as baby bullet do today.

The construction of dedicated HSR tracks in the SF peninsula will mean the end of Caltrain's existing "baby bullet" service. However, electrification plus an expected FRA waiver to operate lightweight non-compliant EMU equipment plus a top speed of up to 90mph means that future Caltrain locals will have the same SF-San Jose line haul time (p2) as baby bullet do today.

This is in keeping with Caltrain's traditional role as a standard-speed commuter railroad and also the only service being planned today. However, if there is sufficient demand, there is no reason why there could not be a Caltrain HiSpeed service in addition to the upgraded locals. After all, the PCJPB does own the right of way in the SF peninsula and could easily negotiate the right to run a certain number of Caltrain-branded trains on the HSR tracks there. It will be many years before long-distance trains will saturate the capacity of the new tracks, so why not use the empty slots for a new genuine bullet Caltrain service, running at top speeds of 125mph in the peninsula? CHSRA has yet to define a speed limit between San Jose and Gilroy, it could be higher in that stretch but nowhere near the 220mph expected through Pacheco Pass and in the Central Valley.

That means Caltrain could deliver a HiSpeed service using cheaper, previous-generation equipment. Note, however, that combining relatively frequent HiSpeed with long-distance express trains only works well if the headways are long enough and the HiSpeed trainsets have superior acceleration and braking performance. One option would be embedded asynchronous linear electric motors in the track infrastructure for a certain distance on either side of the stations. Aluminum plates integrated into the underbody design of the HiSpeed trainsets would be used to leverage this supplemental propulsion without adding significant axle load or drawing excessive amounts of power from the catenaries. During acceleration and recuperative braking, HiSpeed trains would then be hybrid electric/electric vehicles.

The primary purpose of any putative HiSpeed service would be to leverage the HSR tracks in the peninsula and especially, the HSR platforms at the new Transbay Terminal in SF. The downside is that there will only be five HSR station on the route: SF Transbay Terminal, Millbrae/SFO, mid-peninsula (RC, PA or MV), SJ Diridon and Gilroy.

An extension to Hollister would be relatively cheap but require San Benito county to join the PCJPB. That might well entail restricting further residential development to transit villages, ostensibly to protect agricultural acreage but really to protect residential real estate values in Silicon Valley. Given the proximity to the San Andreas fault, buildings in such transit villages would need to feature steel frames and at least 7-8 stories. Earthquakes tend to generate ground excitation at frequencies of around 1Hz, close to the typical base harmonic in bending of buildings in the 4-5 story range.

Running HSR tracks out to Monterey county would be much more expensive due to the interceding coastal mountain range. FRA and CPUC rules plus opposition from UPRR prevent non-compliant equipment from using existing track at standard speeds and stopping at existing stations.

Note that AnsaldoBreda already has a production facility in Pittsburg (Contra Costa county) and is planning to open another in Los Angeles. Siemens has a light rail assembly plant in Sacramento.

Metrolink HiSpeed? In much the same vein, SCRRA, which operates Metrolink, owns the right of way between Palmdale and Redondo Junction plus the one between Fullerton and Irvine. Therefore, if it wanted to, it could negotiate the right to run a certain number of Metrolink-branded HiSpeed trains. The stations served in phase I would be Palmdale, Sylmar, Burbank, LA Union Station, Norwalk and Anaheim. In this case, the primary purpose would be to create a sufficiently large catchment area for Palmdale airport, including visitors to both Los Angeles and Disneyland.

In much the same vein, SCRRA, which operates Metrolink, owns the right of way between Palmdale and Redondo Junction plus the one between Fullerton and Irvine. Therefore, if it wanted to, it could negotiate the right to run a certain number of Metrolink-branded HiSpeed trains. The stations served in phase I would be Palmdale, Sylmar, Burbank, LA Union Station, Norwalk and Anaheim. In this case, the primary purpose would be to create a sufficiently large catchment area for Palmdale airport, including visitors to both Los Angeles and Disneyland.

CHSRA has already mentioned the possibility of local HSR service between LA Union Station and San Diego once the phase II spur is built. It's not yet clear where such a service would park its trains, given that no HSR yard appears to be planned between LAUS and Burbank. The train parking situation in San Diego is also unclear, it might make sense to run tracks all the way down to a terminus/yard in the Southland via the ROW west of I-5.

Amtrak San Joaquin HiSpeed? A third possible HiSpeed service could be Amtrak California-branded and connect Palmdale airport, Bakersfield, Fresno and Merced in phase I, with an extension up to Sacramento in phase II. If CHSRA's arm is twisted enough to build a station in Hanford, at least some of these particular bullet trains would stop there as well. However, considering the rather small populations near the stations served and the need to run at 220mph to avoid impeding long-distance express trains between SF and LA/Anaheim, the Central Valley presents arguably the least compelling HiSpeed proposition, at least in phase I.

A third possible HiSpeed service could be Amtrak California-branded and connect Palmdale airport, Bakersfield, Fresno and Merced in phase I, with an extension up to Sacramento in phase II. If CHSRA's arm is twisted enough to build a station in Hanford, at least some of these particular bullet trains would stop there as well. However, considering the rather small populations near the stations served and the need to run at 220mph to avoid impeding long-distance express trains between SF and LA/Anaheim, the Central Valley presents arguably the least compelling HiSpeed proposition, at least in phase I.

It might make sense if the Merced county station were at Castle Airport, directly inside a new passenger terminal (same as Palmdale) and Fresno Yosemite plus the blighted land beyond its runways were converted into a new mixed used district with excellent transit connections to the HSR station and downtown area. That, however, would be a huge step for Fresno to take and is not currently contemplated.

Moreover, given CHSRA's preference for Pacheco Pass, it might make more sense to defer any development of Castle Airport into a commercial airport to phase II. By that time, HSR will have had a chance to establish itself as a mode of travel and, both Fresno and San Jose might be ready to close their airports to accommodate population growth and eliminate runway blight. Already, e-ticketing and mobile boarding passes mean that check-in at the airport can boil down to dropping off any bags you may have. For passengers hailing from or headed to Silicon Valley, a comfortable 45 minute train trip to Castle Airport with broadband internet access may be preferable to the risk of fog-related delay and a clunky transfer at SFO.

The arrangement would hinge on making Castle Airport the only HSR station in Merced county, such that all trains to and from Sacramento would pass through it. Note that Sacramento's own airport is somewhat constrained by its location smack in the Pacific Flyway, which means it experiences a lot of bird strikes. In addition, it is nowhere near the future HSR station on top of the new STIF. Plans for a light rail line out to SMF call for 13 stops, none of which would be right at the STIF or either of the airport terminals. An HSR trip to Castle Airport would take about 40 minutes.

Thursday, April 30, 2009

HiSpeed Services and Branding

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

New Transbay Terminal Renderings

by Robert Cruickshank

Thanks to Andy at Curbed SF for pointing me to the new design renderings for the Transbay Terminal. Here's how he described it:

[It] shows in more detail in the immediate surroundings of the 1,500-foot-long building, one of whose principal concerns is to not be the dank, enclosed transit station most of us are used to. To that end, large skylights called "light columns" puncture the building from the 5.4-acre urban park on the roof, and penetrate deep into the building— underpasses, notes the architect, also get the airiness treatment. LEED Gold certification is a distinct possibility for the building, whose "urban room" will be similar in scale to Grand Central Station's. The building will almost entirely be naturally ventilated, and there's even talk of tapping into geothermal energy. The park, designed by landscape architect Peter Walker, may also feature a water thing running its length, with fountains spurting whenever a bus passes by underneath. There's room for sky bridges to the park from surrounding buildings, and there'll be a funicular (see: tourist attraction) to take people from ground level to the top.

Ambitious, to be sure, but it's also the right move. A 21st century transit terminal should be an open and inviting place, to suit the renewed interest in mass transit and passenger rail in particular. The folks that redesigned the Ferry Building did a good job with it, but the Transbay Terminal requires a more open design - something that is easy to use and familiarizes San Franciscans and Californians generally speaking with transit as a centerpiece of the city.

Worth keeping in mind the big picture here even as we continue to debate the implementation of the train box and HSR connectivity.

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

DesertXpress EIS and Public Meetings

by Robert Cruickshank

DesertXpress, the company that proposes to build high speed rail from Victorville to Las Vegas, has a Draft EIS ready on their project, and are scheduling some public meetings this week to discuss it (details below). From the DesertXpress press release:

Operating at speeds of up to 150 mph on exclusive tracks along Interstate 15, DesertXpress trains will make the 180-mile trip between Las Vegas and Victorville, California in an hour and twenty minutes. According to the EIS, DesertXpress is forecasted to carry over 10 million people per year by 2015 and over 16 million people by 2030. Ultimately, the system will have a capacity of more than 60 million people per year....

"The project is estimated to reduce up to 360 million pounds of CO2 emissions in the Interstate 15 corridor by greatly reducing automobile travel and replacing it with energy-efficient mass transportation in one of America's most congested transportation corridors," Rogich said.

They believe they can break ground "early next year", which strikes me as a tad bit ambitious. DesertXpress is also aggressively (and in my opinion correctly) pushing back against the concept of building a maglev train on the LA-LV corridor, citing a study for the SoCal Logistics Rail Authority that suggests maglev's costs are going to be too high to afford:

"Maglev has been a thirty-year study of a system that only operates in one other area in the world, which is Shanghai. And we believe the reason it hasn't been further developed in other parts of the world is that according to the BSL Study, the latest cost estimates by public authorities in Germany and the United States put the cost of construction for a Maglev line in the range of $60 million to $199 million per mile - which would bring the cost of the proposed 260-mile Maglev line to US $16 billion to $52 billion - making it the most costly transportation project in U.S. history. On the other hand, the DesertXpress project is estimated to cost from $3.5 to $4 billion, and high speed rail lines are a proven commodity and are successfully operating all over Europe and other parts of the world," said Rogich.

There will be three public meetings this week on the DesertXpress EIS:

Tonight: Las Vegas

5:30-8:00 pm

Hampton Inn Tropicana

4975 Dean Martin Drive

Tomorrow (Wednesday): Barstow

5:30-8:00 pm

Ramada Inn

1511 East Main Street

Thursday: Victorville

5:30-8:00 pm

Green Tree Golf Course Club House

14144 Green Tree Boulevard

Of course, ANY Vegas HSR project, no matter the details, is going to run into opposition from Congressional Republicans who like to use the proposal to criticize federal stimulus spending and trains more broadly. But as the Huffington Post reports, that criticism is usually hypocritical:

While the stimulus was being debated in January, House Minority Whip Eric Cantor called a group of reporters into his office to outline the GOP's objections. As we filed in, we walked past a giant poster ridiculing Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) for allegedly pushing for high-speed rail connecting Disneyland and Las Vegas.

On NBC's "Meet the Press," Cantor called that project an example of "waste and pork-barrel spending."

Yet one man's pork is another man's prudent investment in transit -- and sometimes the same man's.

Asked about high-speed rail at a recent local event in Virginia, Cantor was all thumbs up. "If there is one thing that I think all of us here on both sides of the political aisle from all parts of the region agree with, it's that we need to do all we can to promote jobs here in the Richmond area," Cantor said of the high-speed rail.

One can hope that Senator Arlen Specter's switch to the Democratic Party today will provide a 60 vote majority for HSR funding and render moot idiotic claims like Cantor's.

Monday, April 27, 2009

How Exactly Will HSR Connect To Airports?

by Rafael One of the objectives of the California HSR project is to provide effective connections to existing airports. This should allow airlines to offer connecting train journeys for their long-distance flights. It is also supposed to make secondary airports more attractive to air travelers, but success will depend heavily on getting the last mile transfer between platforms and terminal and other details right.

One of the objectives of the California HSR project is to provide effective connections to existing airports. This should allow airlines to offer connecting train journeys for their long-distance flights. It is also supposed to make secondary airports more attractive to air travelers, but success will depend heavily on getting the last mile transfer between platforms and terminal and other details right.

CHSRA claims the chosen route will achieve this for SFO, Palmdale and Ontario airports. Lindbergh Field (SAN) could now be added to that list, but the purpose of the multimodal transit terminal there is a different one: making it convenient for those arriving by car to take the train rather than fly to other California destinations. Freeing up slots for long-distance flights by displacing short-hop shuttles is another objective for California HSR, but other cities perceive downtown stations as more effective in that context. That is part of the reason why HSR trains will be not be tightly linked to Oakland, San Jose, Fresno, Bakersfield, Burbank, LAX or Sacramento airports.

So let's focus on SFO, Palmdale and Ontario: how exactly will long-distance flights and short-to-medium-distance HSR trips be combined into an attractive value proposition for the traveler? To answer this, we need to look at the following aspects:

- How many long-distance flights will be offered out of each airport?

In the aviation business, there is no formal definition of "long haul". In the US domestic market, it appears to refer to flights of at least 6 hours, e.g. coast-to-coast and transoceanic. California-Hawaii is borderline. Of course, some HSR customers will take a short train trip to connect to a much shorter flight, e.g. to the Pacific Northwest or the interior west. Unfortunately, airports don't publish their statistics down to that level of granularity - at least not free of charge.

SFO statistics reveal the airport handles 20,000-25,000 air carrier movements a month, 2.5-3.5 million passengers, of which 550,000-850,000 are international. The airport experienced robust growth in 2008 and now ranks among the nation's top 10, though passenger numbers still have not recovered to pre-9/11 volume. Note that in 2006/7, SFO commanded much higher fare premiums for long-distance flights than e.g. LAX. About 25% of all passengers flying in or out of SFO hail from or are headed to other California destinations. Factoring in aircraft size, this probably translates to ~1/3 of all aircraft movements.

Ontario is a much smaller airport, with just 7-8 million passengers a year. Most of the long-distance flights appear to be to domestic destinations, with just a few flights to Mexico and other Latin American countries out of the small international terminal.

Palmdale is another of LA's "world" airports, but it recently lost its one and only commercial service (United to SFO) when the subsidy ran out. There is now talk of converting part of the huge area to a solar thermal power plant, though it's unclear if that would prevent the resumption of commercial operations once HSR puts this airport within ~30 minutes of downtown LA. Note that the combination of elevation and high summer temperatures mean that air density at PMD is lower than at LAX, so any fully laden 747s or A380s would need an extra-long runway and a gentle ascent slope to take off. - How many HSR trains will be offered to these airport stations?

In general, this is still very much up in the air. A great deal depends on how easy it will be to find attractive fares, get to the nearest HSR station and, transfer between HSR and flights at the airports. The number and ease of transfers is especially critical for passengers with more than just carry-on baggage.

In spite of the large volume of traffic at SFO, only a subset of HSR trains serving the Bay Area will stop at Millbrae. Expect fares between downtown SF and Millbrae to be artificially elevated to avoid low seat capacity utilization on long-distance trains and cannibalization of Caltrain and BART ridership. The purpose of the station is to provide connectivity for passengers hailing from or headed to destinations well south of SFO, e.g. Silicon Valley, the Central Coast and the Central Valley. Note that CHSRA expects just 3,000 boardings/alightings per day at Millbrae.

Ontario airport is supposed to be on the phase II extension between LA and San Diego via Riverside. HSR trips to and from LA Union Station are expected to take 25 minutes and, CHSRA expects 10,000 boardings/alightings per day. For reference, the FlyAway bus between LAUS and LAX currently takes 30-50 minutes, depending on traffic. However, a new light or heavy rail link via the Harbor Subdivision Transit Corridor could easily cut the budgeted transfer time in half.

It's too early to say what fraction of HSR trains will stop at Ontario, except that CHSRA is planning to use LAUS as a through station, with most trains continuing on to San Diego because of track capacity constraints between Fullerton and Anaheim. San Diegans may well decide to use HSR - possibly including Amtrak Pacific Surfliner at 110mph top speed - rather than fly within California, just so more long-haul flights can be offered out of Lindbergh Field. Taking HSR to catch a plane at Ontario would be an inferior solution for them, though perhaps not for residents of the Murrieta-Escondido area.

Palmdale will be included in phase I. In addition to passengers that would otherwise have used LAX or Burbank, there will be some from the Central Valley. Commercial services to Fresno Yosemite and Bakersfield do still exist, but they are expensive. Even so, it will take some aggressive lobbying of airlines and sweet flight/train bundle deals to build enough ridership, which CHSRA optimistically (?) estimates at 12,000 boardings/alightings per day.

Note that IFF a spur out to Las Vegas ever does materialize, Palmdale would be roughly 75min from Sin City, possibly close enough to serve as a relief airport for McCarran during crunch periods such as major conventions. Ontario via Cajon Pass would be a little further. The bulk of the relief would come from the gradual elimination of flights to California cities on the same bullet train network, comprising almost 1/3 of aircraft movements at Las Vegas. - How will customers discover plane/train combo fares?

If it has not yet done so, CHSRA will presumably request IATA codes for all of its stations so they show up as destinations in airline flight reservations systems. Systems like SABRE are also used as the back-ends to many internet travel portals. It is far more likely that a passenger would discover an HSR trip as a connecting service for a flight than vice versa.

At many airports around the world (e.g. Atlanta, London Heathrow, Paris CDG, Frankfurt/Main, Amsterdam, Vienna, Oslo, Copenhagen, Geneva, Cologne, Leipzig, Kansai (Osaka)), the train platforms are within easy walking distance of the airport terminals. At others, there are frequent people mover connections (e.g. Birmingham UK) to those terminals that are beyond walking distance. However, IATA appears to permit code-sharing even if the train station is many miles away. This is disingenuous as it causes the reservation system to show the plane/train combo journey as having just two legs when it's really three. Many IATA codes for train stations not co-located with airports begin with a Q, X or Z, but this is also not enforced. The use of just three letters also means the most obvious combination may already be in use for an airport somewhere else in the world.

For a sense of how long-haul customers would book a connecting train journey, consider United's GroundLink service to most of France via Paris CDG and SNCF TGV. An enterprising airline could just as easily offer transoceanic service to e.g. Palmdale plus connecting service to any destination on the California HSR network.

In California, it would be desirable to use SFO for the Millbrae, PMD for the Palmdale and ONT for the Ontario HSR station. SAN could arguably be used for Lindbergh Field and BUR for Burbank IFF there's a courtesy shuttle bus. MER for Castle Airport would only be appropriate if CHSRA acquires part of the BNSF row for that segment and a terminal for commercial passenger and/or cargo flights is constructed. - How will these be priced relative to connecting short-hop flights?

The question may not be all that relevant as most passengers will use HSR to connect to final destinations that are too close to be served by connecting flights. The exception will be those in the Central Valley, e.g. SFO - FYI (Fresno Yosemite, previously called FAT). However, those are far more expensive than HSR will be, so expect them to disappear from airline schedules quite quickly to free up slots for long-haul flights that can achieve high seat capacity utilization (aka "load factor"). Passengers will also prefer the trains because they will run more frequently, more than offsetting the longer trip time by cutting the layover interval. - How will passengers get from the train platforms to their gates?

In SFO's case, BART really does run into the airport. However, anyone arriving at Millbrae by Caltrain currently needs to transfer to BART, execute a cross-platform timed transfer at San Bruno and then a third transfer to the Air Train to reach the check-in counters. See here and here for the gory details.

One of the reasons the BART shuttle between SFO and Millbrae was discontinued is that the unions insisted that it constituted a line in its own right, so drivers should be permitted to take a 15-minute break at the end of each journey. Alternatively, each train would have to be operated by two drivers, each twiddling their thumbs more than 50% of the time.

Running the AirTrain out to Millbrae would be very expensive, so either a BART shuttle or a SamTrans (?) bus would have to be paid out of airport taxes if that station is to share the IATA code with the airport.

At Ontario, the last mile transfer depends entirely on the right of way CHSRA can obtain through the San Gabriel Valley. The plan of record is to leverage the UPRR Colton alignment that runs right past the gigantic car park in front of the three terminals on S Moore Way and E Terminal Way, respectively. Given how spread out the terminals are, the most likely solution would be a shuttle bus or people mover that also serves long-term parking. This approach is still viable if HSR ends up in the I-10 median. However, if HSR were forced even further from this secondary airport, e.g. to the CA-60 median, it could not act as an effective feeder. In that case, it would make more sense to extend the starter line from Fullerton to Riverside and San Bernardino, with a view to one day reaching Las Vegas. Any money saved should then be put toward upgrading the Pacific Surfliner route to higher speeds or else, on a spur down to San Diego at Corona.

In Palmdale, the existing terminal is located almost 3.5 miles from the Metrolink station. The most likely connection would be a shuttle bus. Of course, now that commercial operation has anyhow ceased, it might make sense to build a brand-new terminal near Sierra Hwy/Ave N with detour tracks for HSR trains at grade and check-in/baggage retrieval on a concourse level. Note that Palmdale could also serve as a high speed cargo transshipment point, as the northern terminus for HSR trains serving only Southern California and as a maintenance facility.

In essence, much the same logic would apply for Castle Airport in Merced county - right now, there's a long runway and a nearby rail line but not much else.

Remote secondary airports have little or no chance of commercial success without a high speed train station within walking distance of the airport concourse. Even then, some caution is in order: the spectacular Satolas station was built right next to the airport in Lyon, France, in the 1980s. The hope was that the TGV would attract additional passengers from south of Lyon to the airport such that airlines would offer more international flights.

However, in one of France's worst transportation planning failures, SNCF/RFF never constructed the turn-off that would have permitted regional TGV service between downtown Lyon (Part-Dieu), the airport, the Rhône Valley and beyond. As a result, Lyon was never able to emerge from Paris' long shadow. In 2010, a new express light rail service will finally provide a 20-minute transit link between downtown and the airport but that's no more than a consolation prize.

The lesson from Satolas is that a secondary airport without a substantial local catchment area will struggle to attract the flights that would prompt passengers to ride a train to the airport in the first place. It's a chicken-and-egg situation that can only be overcome with a plan for integrated service. This has to be driven by one or more innovative airlines collaborating closely with one or more rail operators to offer a combined service that is hassle-free, fast, punctual and competitively priced. The notion that a government agency like CHSRA or LAWA can "build it and they will come" is false. - Where will check-in and security screening happen?

Some operators in Europe (e.g. Deutsche Bahn) do provide flight check-in facilities at selected train stations, but all security screening still happens at the airport. In 2010, the European rail networks will be opened to international competition. At that point, Air France and others intend to compete directly with Eurostar on the London-Paris route, where baggage and passenger screening is already performed at the train stations because the UK is not a signatory to the Schengen agreement. However, the rail and airport security zones are currently not equally strict nor integrated, so passengers will still probably have to submit to screening twice.

Afaik, no rail operator anywhere allows passengers to take care of flight check-in formalities on board the train to save time. Reliable wireless internet connections are still a new phenomenon and there are also logistical issues, e.g. with weighing bags.

However, consider this scenario: you go online and book a train/flight combo ticket with XYZ airline, which has decided to operate out of a secondary airport with an integrated HSR station. You print out your ticket/write down your confirmation code. At the appropriate time, you board the train with your baggage. Once you're underway, you head to the cafe car, which features a courtesy desk where you can check in for your flight. In addition to your boarding pass(es), you receive self-adhesive baggage tags that you need to attach yourself. Upon arrival at the airport, you need only drop off your bags. The person there will check that your bags are in order (size, weight, condition) and scan the bar code before letting you proceed. The airline would not be responsible for lost bags prior to this point. - Will baggage be checked through to the final destination?

Train stations that permit combined train/plane check-in on the outbound leg also provide the boarding passes and baggage labels for the flight. However, in most cases passengers still have to take their bags onto the train themselves. One exception is Vienna, Austria, where you can check your bags the night before or, up to 75 minutes before the shuttle train leaves for the nearby airport. Baggage is forwarded automatically to the airport's handling facility. Returning passengers do have to pick up their bags at the baggage carousels as usual, though.

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Gavin Newsom on HSR

by Robert Cruickshank

In a meeting with bloggers yesterday at the California Democratic Convention here in Sacramento, Gavin Newsom answered questions on a wide range of topics, including one from Becks who writes at Living in the O on restoring transit funding.

(I'm the one sitting next to Gavin)

Newsom's answer was that California is a wealthy state, and that we should be able to find the means to support transit. He pointed out the absurdity of the federal stimulus supporting spending on infrastructure and rolling stock but not on operating expenses - "we can buy buses but can't pay people to drive them." Newsom specifically mentioned high speed rail in his answer - that when he was younger he took a trip to Europe and rode their high speed trains, but when he came back "all we had was Caltrain." Newsom was a strong supporter of last fall's Proposition 1A, and has been one of the leading forces behind getting the Transbay Terminal done. Newsom wants to build HSR as governor of California - if he won two terms he might be able to preside over the opening of the LA-SF route in 2018.

Of course, his leading rival for the Democratic nomination for governor, Jerry Brown, is also a longtime supporter of HSR, having created the state's first HSR project back in the early 1980s when he was governor. Both men, if they became governor, would presumably be strong supporters of HSR.

I'm headed back to Monterey on the Capitol Corridor this afternoon - use this as an open thread.

Saturday, April 25, 2009

California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard

The LA Times reports that the California Air Resources Board has just released a complex new environmental regulation called the "Low Carbon Fuel Standard" (LCFS). This is relevant for High Speed Rail in that it will inevitably raise both vehicle and fuel prices for cars and trucks in the medium and long term. That in turn should boost ridership on all types of mass transit and the popularity of transit-oriented real estate development statewide.

The LA Times reports that the California Air Resources Board has just released a complex new environmental regulation called the "Low Carbon Fuel Standard" (LCFS). This is relevant for High Speed Rail in that it will inevitably raise both vehicle and fuel prices for cars and trucks in the medium and long term. That in turn should boost ridership on all types of mass transit and the popularity of transit-oriented real estate development statewide.

Objectives

One objective is to diversify the fuel sources for the millions of internal combustion engines powering motorbikes, cars and trucks in California, away from (mostly) imported fossil crude oil and toward substitutes derived from locally grown energy crops and agricultural waste streams or, from other local, renewable sources of primary energy. Considering that California requires so-called "boutique" gasoline with special additives to curb summer smog, it could not import finished product from out of state or abroad if one of its refineries went offline. Therefore, the diversification of fuel sources is a priority both for energy security and for the state's balance of trade.

A second objective is to reduce net carbon emissions of each gallon of fuel pumped at California gas stations to help meet climate policy goals. Vehicles fueled partially or wholly by substitutes must of course not emit more toxic compounds than those running on conventional oil distillates, but their net CO2 emissions will be lower. The savings accrue not at the tailpipe when the vegetable matter that is used as a feedstock for the alternative fuel production grows back a year later. This is why ARB selected the GREET model for the entire carbon life cycle of each type of fuel. For biofuel compounds, it also takes land use and food web impacts into account.

Note that California's new low carbon fuel standard does not aim to directly reduce total vehicle miles driven, nor to increase vehicle occupancy rates, nor to reduce aggregate net CO2 emissions from ground transportation in the state. Some or all of these outcomes may materialize indirectly as a result of higher vehicle and/or fuel prices.

Exempt Industries

The aviation industry was apparently exempted from the new state regulations. Part of the reason may be that jet fuel is subject to very stringent quality standards for safety reasons. In addition, federal laws and international treaties restrict individual states' ability to tax aviation fuels and/or enforce the use of fuel substitutes in blends or neat form.

In general aviation, there is a desire to phase out 100 octane low lead (100LL) AVGAS, but all substitutes - 91 octane gasoline, methanol, ethanol - require significant modifications to airframes, fuel system components and engines. In the US, any retrofit kits would have to be certified by the FAA, so the industry is moving toward new designs featuring turbocharged diesel engines that can run on either diesel or jet fuel. Some US airports have already stopped selling AVGAS, perhaps in a thinly disguised effort to free up more slots for commercial flights.

Off-road, marine and locomotive fuels are also not covered by the new regulation, nor is the US military.

Natural Gas, Hydrogen and Electricity

Returning to trucks and cars: natural gas, hydrogen and electricity are all included in the list of alternative transportation fuels in the new regulations, which do not consider the details of the alternative drivetrain technologies required to take advantage of them. The GREET models for these fuels do account for how these substitutes are produced and distributed.

Regular natural gas is less carbon-intensive than gasoline but it requires some engine modifications. In addition, achieving an acceptable operating range of ~200 miles between fill-ups requires heavy, bulky and expensive fuel tanks that can withstand 250-300 bar (3630-4350 psi) of pressure plus a network of gas stations equipped with the requisite compressors. On the other hand, biomethane blended with a small amount of propane is the only cellulosic biofuel that could easily be produced in bulk today. EU regulations already permit producers to feed it into the existing European network of natural gas pipelines.

The cheapest way to produce hydrogen is steam reforming of fossil natural gas, but this releases copious amounts of CO2. There may still be a niche application for it in the context of blends of natural gas and a small amount of hydrogen, e.g. Hythane. Relative to CNG, the hydrogen additive accelerates flame propagation and ensures near-complete combustion while improving thermodynamic cycle efficiency. It is best used in efficient homogenous lean-burn spark ignition engines equipped with oxidation catalysts and NOx traps or SCR systems originally developed for diesel engines. To avoid hydrogen embrittlement, special alloys or composite materials must be used to contain fuels containing hydrogen.

This also applies to the entire distribution chain of neat hydrogen and the 700 bar (10150 psi) pressure tanks deployed in fuel cell vehicles (FCVs). However, thanks to the GREET model, hydrogen will now have to be produced using electrolysis of fresh water using electricity from controversial nuclear or expensive renewable sources. Thus, the LCFS virtually guarantees that FCVs will remain a niche phenomenon.

That in turn could create more of a market for vehicles that can store such zero-carbon electricity directly in on-board battery banks. High-volume manufacturers prefer the more expensive and less energy-dense chemistries based on nickel metal hydrides (NiMH), lithium-manganese spinel or lithium nanophospate to banks of commodity lithium-cobalt ion cells found in cell phones and laptops (cp. Tesla Motors). To understand why, watch these videos of nail penetration tests of commodity vs. automotive-grade Li-ion cells, simulating a severe crash scenario.

Regardless of chemistry, all automotive applications of advanced traction batteries have to be maintained at intermediate states of charge (30-90%) and forcibly cooled to near room temperature to ensure they will last for the lifetime of the vehicle. The battery packs used in electric bicycles and scooters are much smaller and cheaper, but owners typically have to replace them after a few years.

Implications for Oil and Utility Companies

Santa Barbara County recently reversed itself on a controversial decision to lift a ban on new offshore drilling in the area. From the oil industry's perspective, the new LCFS adds insult to injury as the carbon life cycle analysis also exposes oil produced from tar sands (cp. Athabasca, Canada) as incredibly carbon-intensive. Developing the US Navy's vast oil shale deposits in Colorado would be even worse.

The new rules point in exactly the other direction: they require refineries to cut the net carbon emissions from their products by 10% in the next decade by blending in renewable compounds or, by selling neat substitutes alongside traditional oil distillates. The latter option would permit oil companies to set up networks of rapid recharge stations for battery electric vehicles, though fire safety considerations will require these to be located sufficiently far from gasoline pumps. Note that oil companies could presumably also comply by taking equity stakes in utilities or else, in specialized start-ups such as Better Place.

However, it's far more likely that oil companies will invest in emerging, relatively benign liquid hydrocarbon technologies such as cellulosic ethanol that are more compatible with their existing distribution infrastructure and the existing vehicle fleet. The fuel systems and engines of all cars and trucks sold in the US since the 1970s can tolerate E10 (10% ethanol) blends. In addition, a loophole in CAFE rules allows auto manufacturers could avoid gas guzzler taxes for popular SUV and pick-up models equipped - at modest expense - with seals and gaskets made from materials that can tolerate blends as high as E85. Millions of car and truck owners are not even aware that their vehicle is already flex-fuel capable.

Unfortunately, one of the biggest headaches presented by cellulosic feedstocks is that they are usually solid and therefore expensive to transport to a large central biorefinery. Moreover, the end product ethanol is highly hygroscopic i.e. it attracts moisture from the ambient air. To avoid corrosion risks, it must be distributed via truck or freight rail instead of existing gasoline pipelines. In addition, storage tanks at gas stations must contain stirrers for fuels containing ethanol. California refineries currently purchase most of their ethanol from the Mid-West, where it is produced from glucose contained in corn kernels - competing directly with applications in the food web. Cellulosic ethanol avoids this problem, but large amounts of energy are needed to increase the surface area of readily available feedstocks like corn stover, switch grass etc. Only then can bacteria begin to break the cellulose down into simple sugars and then ferment those into ethanol. Fermentation into the more desirable biobutanol is in a much earlier stage of microbiology R&D.

An alternate, more easily scalable route is the conversion of cellulosic waste streams, including lignocellulosic biomass, into synthesis gas, a mix of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. This can be converted in Fischer-Tropsch reactors into a variety of useful fuels including synthetic natural gas (SNG) and, alkanes suitable as bulk substitutes for diesel, even gasoline. Unfortunately, F-T is highly exothermic (i.e. inefficient) and also not very selective (i.e. you get lots of worthless by-products) and the results become worse as you scale plants down to reduce the overheads associated with feedstock logistics. This makes F-T unattractive in the context of the carbon life-cycle analysis at the heart of California's new LCFS, unless both the waste heat and the waste CO2 can be leveraged for secondary processes such as steam generation and algal oil production.

Implications for Car and Truck Manufacturers

Gasoline and diesel are the dominant fuels for internal combustion engines used in ground transportation for two very simple reasons: low cost and high energy density. They are also very well suited to precisely controlled combustion in spark and compression ignition engines, respectively. All of the technologies involved have been the subject of continuous refinement for over a century. In addition, there are well-established networks for fuel production and distribution plus vehicle maintenance and repair.

Auto manufacturers therefore also prefer incremental changes, e.g. new and retrofit fuel systems for ethanol and biodiesel (FAME). Only modest changes to fuel pumps, combustion control and/or exhaust gas aftertreatment are required for these. Keep in mind that fuels with lower energy density (e.g. E85) are consumed at higher rates, so MPG goes down, as does range on a full tank.

The problem is that lawmakers and regulators see a need to go much further much faster, in terms of both toxic emissions and energy security/climate change. To that end, they are pushing concepts such as hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and various types of electric hybrids using both mandates (Zero Emissions Vehicle Program) and incentives (Tax Credit Programs) to overcome substantial technical hurdles and encourage the construction of new distribution infrastructure.

Battery electric vehicles can be charged off the existing grid, if you happen to have a garage or reserved parking space. Unfortunately, using a standard 110V/15amp household circuit require a charge times of 4-8 hours for an operating radius of just 40-100 miles, depending on vehicle mass, aerodynamics and how aggressively they are operated. High acceleration/deceleration rates and high speeds are very detrimental to range, as are hotel loads such as cabin heaters and A/C. Fortunately, research has shown that privately owned motor vehicles are typically operated less than 2 hours out of every 24 and, cover less than 30 miles on most days.

General Motors is betting the farm on a technology that combines a full battery electric drivetrain with a small gasoline engine attached to a generator to extend vehicle range. This concept was first presented in the Lohner-Porsche Mixte Hybrid in 1901. It remains to be seen if consumers will be willing to pay a premium of $15k for a Chevy Volt over a comparable conventional Malibu, even if the federal government provides a super-generous $7500 tax credit for early adopters. Even if your daily commute distance (15-20 miles each way) allows you to very nearly deplete the grid electricity charge without firing up the gasoline engine, it will take many years to recoup the additional initial investment as long as gasoline remains comparatively cheap.

Supply regulations like LCFS that indirectly force consumers to shell out for motor vehicle features that they would not purchase voluntarily tend to reduce both profit margins and annual unit volume. Approaches that deliver fiscally sustainable changes in consumer demand would ultimately deliver a greater aggregate impact on climate policy while also making a smaller auto industry more profitable.

Implications for Transit and High Speed Rail

As indicated at the beginning of the post, the new Low Carbon Fuel Standard will above all make buying and operating a motor car more expensive, because essentially all alternative fuel and propulsion technologies cost more than the status quo. This means California families will likely own fewer and on average, older cars and trucks than is the case today.

In the long run, high school and university students may not be able to afford owning a car. Instead, they make do with a scooter or electric (folding) bicycle instead. In addition, simple economics may force them to use local and regional transit more frequently. From there, it is a just a small step to riding high speed rail instead of catching a short-hop flight. Later, this new generation may well prefer living in an apartment in a walkable transit village to their parents' dreams of a large free-standing house in the suburbs where cars are the only way to go anywhere, at least in the winter months.

Electric passenger rail is today and will likely remain the only transportation technology capable of moving millions of people across hundreds of miles quickly, safely and in comfort while making time spent in transit productive via reliable broadband Internet access. The much-ballyhooed zero tailpipe emissions vehicle is actually a very old hat, the hard part is getting urban planners and real estate tycoons to revert to thinking in terms of linear rather than area development patterns, i.e. dense transit villages instead of low-rise sprawl across a grid.

Coda: The Future of the LCFS

If history is any guide, it is very likely that a variety of business interests will lobby California politicians as well as ARB bureaucrats to make incremental changes to the complex new regulation. The cumulative effect will likely be a gradual watering-down, even if crass excesses like the aforementioned E85 loophole are avoided. If the state is serious about reducing its net carbon emissions, by far the most effective approach would be to raise fuel taxes as Japan and European countries did long ago.

Unfortunately, very few politicians are prepared to be honest with voters, so they favor new regulations such as this one. Moreover, forcing industry to lobby them fills their campaign coffers.

It is not yet clear if other states will adopt California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard in addition to its strict limits on toxic tailpipe emissions. Note also that the Obama administration has recently given EPA jurisdiction over CO2 emissions, which may well translate to fleet average limits per mile that will render CAFE (administered by USDOT) and the gas guzzler tax (administered by the US Treasury) essentially irrelevant. That sets the stage for a new arena of jurisdictional conflict between EPA and California ARB.

Friday, April 24, 2009

CHSRA and Peninsula Cities Agree On Planning Process

As reported by the Mercury News:

In the first signal that individual Peninsula cities will have a direct voice in high-speed rail planning, a state official Thursday unveiled plans to launch working groups in which local representatives will help shape the massive project.

San Mateo, Santa Clara and San Francisco counties would each get a working group that would meet eight times with high-speed rail officials between May and April 2011, said Tim Cobb, project manager for the San Francisco-to-San Jose section of the high-speed rail line....

Cobb said after the meeting that the working groups were based on similar setups already in place in Southern California, where planning of the train is further along. The "technical working group" meetings will take place during project milestones, such as when key planning documents are released.

The Santa Clara County group will consist of representatives from the five cities along the Caltrain line — including Palo Alto and Mountain View — plus the county government. The San Mateo County group will be made up of representatives from the 11 cities along the train tracks, as well as a county official.

It would be up to the cities and county governments to choose who would be their representative, said Cobb. Ideally, each delegate would remain through the duration of the planning process, he said.

Obviously this is the right thing to do, although as usual, the devil is in the details. It's good that the cities have a formal seat at the table with CHSRA, and that should do much to ease the concerns of the cities that their concerns are being ignored. As I've argued before though, that never really was the issue here. Instead the issue is the desire of some Peninsula cities to exercise a veto over the project and interject themselves into decisions, such as operations, that they really have no place or right dictating about (and make no mistake, many of these cities will want to dictate terms).

It will be very interesting to see how this group approach proceeds, especially when the astronomical cost of tunneling becomes clear. That's when the big fight will take place.

The above was announced at sn HSR info session in Belmont last night. Not much else took place, although this was worth noting:

While going underground in general is expensive, it might be worth it in areas where there are many grade separations with which to work.

“At this stage, I don’t think we can talk about the costs of the alternatives yet and I don’t think we want to,” said Tim Cobb of the High-Speed Rail Authority.

At the same time, even if a tunnel is listed among the alternatives, cost will likely be the deciding factor. We'll see what happens.

Note: This weekend I'll be here in Sacramento for the California Democratic Party convention. If there's any HSR news to report, I'll be sure to post it here. Otherwise I'll leave you in the capable hands of Rafael and the open threads!

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Upcoming Public Rail Meetings

Next week in Los Angeles there will be two public events to showcase and build support for passenger rail in California, high speed rail included. Both are worth attending, especially if you live in Southern California and have the time.

First up is the May 1st 21st Century Transportation for Los Angeles Conference being hosted by CALPIRG. It'll be from 10-3 at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels at 555 W. Temple in downtown LA. Among the speakers will be Quentin Kopp.

The next day, Saturday May 2 at 9:15 AM, also in downtown LA (this time at Union Station) is the RailPAC and NARP joint meeting, with a general topic of Steel Wheels In California. Some of the leading figures in passenger rail will be speaking there - Joseph Boardman, the new CEO of Amtrak; Bill Bronte, who heads Caltrans' Division of Rail, and several other LA-area rail figures. Specifically for HSR, Rod Diridon of the CHSRA board and Bruce Armistead of Parsons Brinckerhoff will be there to talk about the HSR project.

I'm going to try and attend both events, but it's unclear whether I'll actually be able to (the next week and a half is shaping up to be unusually busy for me). Regardless, if you're in Southern California, you ought to consider attending one or both of these excellent public events, a good opportunity to learn about the status of the HSR project - especially since the CHSRA hasn't yet held public workshops in SoCal just yet.

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Earth Day 2009: Focus on Electricity

Ever since 1970, April 22 has marked Earth Day in the United States. The objective has always been to raise awareness of environmental issues and to prompt individuals to take actions that benefit the environment in some way.

Ever since 1970, April 22 has marked Earth Day in the United States. The objective has always been to raise awareness of environmental issues and to prompt individuals to take actions that benefit the environment in some way.

Today marks the first Earth Day of the Obama administration. The President will head to Iowa to promote renewable electricity generation, specifically wind farms. This is part of a larger strategy to gradually wean the US economy off fossil fuels in general and oil in particular. Reducing US dependence on these finite resources is an essential contribution to both climate policy and national security. The administration's energy-cum-green-collar-jobs legislation is already making its way through Congress, albeit slowly.

Of course, any sensible energy policy needs to address not just how electricity is generated but also the total amount used. Without aggressive conservation, renewable electricity - hydro, wind, solar, geothermal, biomass - will always struggle to cover more than a tiny fraction of total demand.

Visit msnbc.com for Breaking News, World News, and News about the Economy

Florida Power & Light has embarked on a $200 million project to install "smart meters" in all homes in Miami-Dade county. Each meter contains a WiFi transceiver that allows consumers to track their electricity usage with software installed on their PC. Knowing when they consume which amount of electricity on a given circuit - mapped to specific rooms or appliances - makes it much easier for them to identify and eliminate power hogs.

California's Bay Area and San Diego are just as exposed to the threat of slowly rising sea levels as south Florida. Yet it is air conditioning demand in the hot inland areas of both states that places enormous strain on the utility companies on the 10 hottest days of the year. In California, aggregate demand can jump by as much as 50% when people return home in the late afternoon and switch on their central A/C unit, often at full power to bring temperatures back down quickly. According to a KQED Quest radio report, simply selecting a device that is optimized for the temperature and humidity range in a particular area can save 20% on A/C-related electricity consumption. There are more than just cost savings here, because the rarely-used power plants that exist purely to cope with extreme peak demand have to deliver that power quickly and reliably - which means using gas turbines. While these could run on stored biogas, the regulatory structure still favors the use of fossil natural gas.

There are plenty of other examples of scope for structural reductions in electricity consumption in California:

- for new buildings, solar architecture encompasses everything from avoiding large south-facing windows to insulation to self-shading, water features and vegetation, all in an effort to keep the indoor and interior courtyard areas naturally cool during the summer months

- in some locations, apartment complexes and businesses can already choose to deploy green roofs with drought-resistant plants supported by recycled water to provide natural insulation

- the pumps used to transport water from the Sierras to Southern California and the Bay Area consume around 2% of the state's total, so encouraging newcomers to move to where the water flows naturally is a good idea - especially since it will also discourage the agriculture of thirsty crops

- Internet data centers in California also consume around 2% of the state's total, of which about half is A/C load. Emerging liquid cooling technology for servers and mass storage units should help bring that down.

Of course, all of the conservation measures described above relate to stationary devices. Small mobile devices like cell phones and laptops, even bicycles, can easily be powered using grid electricity stored in batteries. The same is not true of large vehicles - the high cost, limited range and safety aspects of large battery banks are the reasons why virtually all cars and trucks on the market use internal combustion engines that rely on oil distillates. Commercial airliners rely on kerosene-guzzling jet engines, though when they are fully booked, the newest long-distance aircraft do consume less per passenger-mile than single-occupant cars do on the highway. By contrast, short-hop flights are among the least energy-efficient modes of transportation. That means aggressive conservation and/or switching to electricity is especially important for the transportation sector.

While some bus systems have been electrified using overhead catenaries, it is far more typical of rail transit: streetcars, light rail and subways. In the US, regular heavy rail has been electrified in the NEC but virtually nowhere else. The California bullet train system will be electrified, if only because it's the only way to achieve 220mph. At full capacity, the fully built out network is epxected to require around 480MW of electrical power, roughly 1% of the total installed generating capacity in the state today.

In keeping with the spirit of Earth Day, CHSRA wants it to run entirely on renewable electricity, something that will be easier with energy conservation in stationary applications. In this context, 100% renewable means that for each kWh consumed during a given time period (e.g. 1 year), there must be a corresponding kWh produced at a wind farm or other renewable source. In terms of global warming impact, it isn't strictly necessary that there be sufficient active renewable electricity generating capacity to power all of the trains at any given instant. This arbitrage is exactly where President Obama's smart grid concept comes in, something German scientists have already been working on for a while. For political reasons, that country wants to phase out both nuclear and coal-fired generating capacity.

In the context of a busy rail system, brake energy recuperation from one train to others on the same segment further improves overall energy efficiency, especially if the grid operator gets 20-30 seconds advance warning of a train braking. That information is readily available to the rail infrastructure operator, except in emergency situations.

For all these reasons, I couldn't agree more with this article in today's Des Moines Register, entitled simply:

To push clean energy, back high-speed rail

Even diesel-based "emerging HSR" is a lot more efficient than cars are at comparable occupancy rates. Considering that most cars have just one occupant, that's a low hurdle. Electrification just makes trains an even more strategic element of the passenger transportation mix going forward.

Update by Robert: This seems like a good occasion to remind folks of the CHSRA renewable energy study that we discussed last September. The report goes into detail on just what is necessary for the CHSRA to achieve 100% renewable energy for their system, a goal the Authority's board adopted last fall.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Is Vegas HSR Out of the Obama HSR Stimulus Derby?

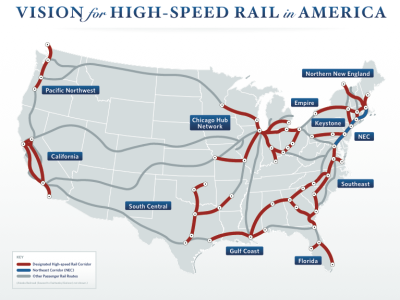

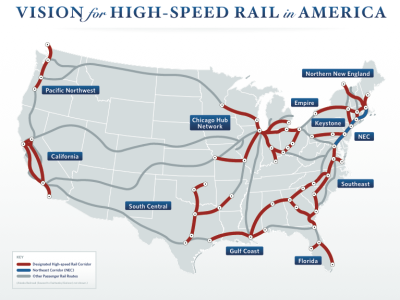

When President Obama announced his HSR Strategic Plan last week, the USDOT report that accompanied the announcement included this map of HSR corridors, based on the 2001 map:

One route you don't see on that map is LA to Las Vegas. Does that mean the project, which right-wingers tried to generate controversy around back in February, is ineligible for the HSR stimulus money? That's the topic examined in an article in the Barstow Desert Dispatch:

The Obama administration’s strategic plan for spending the $8 billion in stimulus funding allotted to high-speed rail projects makes no mention of a proposed rail line from Anaheim to Las Vegas that would stop in Barstow.

Project proponents are still hopeful that some of the funds may come their way.

The plan released Thursday by President Barack Obama and U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood lists 10 designated high-speed rail corridors where projects are eligible to receive funding, none of which include the Anaheim to Las Vegas route.

So does this mean that the map shown above really will determine HSR funding priorities? Well...maybe not:

Lori Irving, a spokeswoman with the U.S. Department of Transportation, said projects that are not located in the existing corridors may still be eligible to compete for some of the stimulus funds.

And the backers of the maglev train are optimistic:

Bruce Aguilera, chair of the California-Nevada Super Speed Train Commission, which is tasked with moving the Anaheim to Las Vegas train project forward, stated via email that the project proponents still plan to file a request for stimulus funds and expect to be eligible.

“We have a plan and (are) moving fast to have the first leg built during the president’s first term,” Aguilera wrote.

Of course, unless they suddenly abandoned the maglev plan in favor of Desert Xpress and are planning to break ground this afternoon, I'm having a hard time seeing how they'll have the first leg built by the end of 2012.

I wouldn't be surprised if the LA-Vegas corridor got some amount of startup funds, to complete environmental design work - perhaps as much as $100 million or more (but certainly no more than $500 million). But with so many other corridors also looking for funds, with a much more developed and realistic plan - and sorry folks, maglev on this scale really is gadgetbahn - I am hard pressed to see how Vegas HSR is going to get very much out of the USDOT process.

The more I look at this, the more I think that if Vegas HSR is going to happen, the state of Nevada is going to have to take the lead in stepping up to fund a big chunk of it. If Obama is somehow able to create a stable funding source for HSR then that could put Vegas HSR in the pipeline - but it could also take 20 more years to bring it to fruition. If Vegas interests (that would be the casinos) want it to happen sooner, they'll need Nevada to help accelerate the timeline.

That will eventually raise the issue of how much California wants to spend on Vegas HSR. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a long standoff between Caltrans and NDOT over widening Interstate 15 between Barstow and the state line. California did not want to spend money on that project which benefits an out-of-state interest, especially with so many other road projects around the state clamoring for money. Eventually NDOT agreed to help pay and the widening projects were undertaken.

With Vegas HSR, Nevada and the feds could reasonably argue that California should put up more of the money since the route would serve California residents for in-state trips (especially if they use a Cajon Pass routing - Victor Valley residents would have a way to commute to and from jobs in the LA Basin). I'm not sure that's a high priority HSR corridor for this state, and I would be wary at this time of committing California to funding Vegas HSR. Ideally we could revisit the matter around 2020. But Vegas' timeline is much more aggressive, and I am betting we'll see Nevada leaders pushing California for financial commitments much sooner.

Something to keep in mind.

Monday, April 20, 2009

How The AVE Is Changing Spain

Today's Wall Street Journal offers a fascinating look at how Spain's AVE high speed trains are changing that country in some interesting and generally positive ways. As you know from our previous posts on the topic, not only do I have a personal affinity for the AVE, but their dramatic success in a nation whose pre-AVE travel habits, population densities and natural geography are very similar to those of California is a strong indicator of how HSR will be successful here in California.

To sell his vision of a high-speed train network to the American public, President Barack Obama this week cited Spain, a country most people don't associate with futuristic bullet trains.

Yet the country is on track to bypass France and Japan to have the world's biggest network of ultrafast trains by the end of next year, figures from the International Union of Railways and the Spanish government show.

Although the AVE was initiated by a Socialist government in the early 1990s, both the PSOE and the right-wing Partido Popular are strong backers of the AVE trains, and now Spain will have a large network of fast electric trains connecting its major cities. Already Sevilla, Málaga, and Barcelona are linked to Madrid - Valencia, Bilbao, and some of the northwestern cities are next in line. But they don't plan to stop there:

But the AVE-which means "bird" in Spanish- proved to be a popular and political success. Politicians now fight to secure stations in their districts. Political parties compete to offer ever-more ambitious expansion plans. Under the latest blueprint, nine out of ten Spaniards will live within 31 miles of a high speed rail station by 2020.

That's some amazing penetration of the HSR network that is planned for the next ten years. And it's even more fascinating considering that until the first AVE line opened in 1992, Spain's travel habits closely resembled those of California:

And although those numbers stem from the Madrid-Sevilla AVE line, they've been repeated in particular on the Madrid-Barcelona line, which has taken nearly 40% of the market on what was one of the world's busiest air routes.

The WSJ article suggests that the AVE has not only reshaped travel habits, but social and economic habits as well, maybe even cultural habits:

"We Spaniards didn't used to move around much," says José María Menéndez, who heads the civil engineering department at the University of Castilla-La Mancha. "Now I can't make my students sit still for one second. The AVE has radically changed this generation's attitude to travel."...

The AVE was originally designed to compete with the airplane for commutes between major cities around 300 miles apart. But the biggest, and least expected, effect of the AVE has been on the smaller places in between.

Perhaps the most striking example is Ciudad Real, a scrappy town 120 miles south of Madrid in Castilla-La Mancha which, Mr. Ureña says, "had completely vanished from the map." In medieval times, the town was a key stopover point on the route between the two of most important cities of the time, Córdoba and Toledo. But the railway and the highway south later bypassed the town, and Ciudad Real began to wither.

Now it has an AVE station that puts it just 50 minutes away from Madrid, and Ciudad Real has come alive. The city has attracted a breed of daily commuters that call themselves "Avelinos." The AVE helped attract a host of industries to Ciudad Real, and the train is full in both directions.

Ciudad Real is a town somewhat analogous to Merced, and one can imagine that the California HSR trains will make UC Merced a more attractive option to students in the Bay Area and in Southern California. You can be sure that Central Valley cities are looking to the experience of places like Ciudad Real as a possible model of how their towns can provide more stable and lasting economic growth built around the high speed train.

Of course, the article does mention some criticism of the high speed trains:

Not everyone is pleased. ETA, the militant Basque separatist group, has said it would target anyone involved in the construction of a high-speed train line that will connect the restive northern region with Madrid and France. In December, ETA killed the owner of a company working as a contractor on the project, and in February detonated a bomb at the headquarters of Ferrovial SA, another contractor working on the project.

This issue is not so relevant to California, for obvious reasons, and it's worth noting that ETA's concern is that the AVE will be so successful that it will erode the Basque Country's autonomy by linking it more closely with the rest of Spain. The other main criticism voiced is that Spain's HSR focus is leaving other transportation infrastructure less funded:

Other, nonviolent critics say the country's massive investment in high speed rail has come at the expense of other, less-glamorous forms of transportation. Starved of funds, Spain's antiquated freight-train network has fallen into disuse, forcing businesses to move their goods around by road. That means the Spanish economy is unusually sensitive to changes in the price of crude oil.

And yet that's not really an argument against the successful HSR project - instead it's an argument for the investment in freight rail. It doesn't have to be an either/or proposition.

Critics say the AVE will never stop losing money. Even its backers say high-speed rail can only be economical if the state bears much of the construction costs. But they say the train's benefits-lower greenhouse-gas emissions, less road congestion and, in Spain's case, greater social cohesion and economic mobility-make it an investment worth making.

Of course, Spain's roads were built with state money as well. Here in California our airports and freeways were built with state and federal money. Freeways are not expected to turn a profit. The whole notion that our transportation infrastructure should turn a profit is absurd, even if most HSR systems break even or generate surpluses, more than covering their operating expenses. And that's a sensible approach - the state makes the investment in the infrastructure, and the ongoing operations are self-sustaining.

Spain is like California in another way - it's getting extremely hard hit by the global recession. Like California, Spain experienced a significant property bubble and is now paying the price with high unemployment. I don't know how this will impact the ambitious AVE construction plans. But at least Spain spent the last 20 years investing in sustainable transportation - whereas California frittered away its economic boom on sprawl, roads, and tax cuts. Spain is in a better position to weather the economic storm and recover from it thanks to its investment in the AVE.

It's not too late for California, of course. With Prop 1A and President Obama's support we can start down the trail Spain blazed nearly 20 years ago. HSR will change California in interesting ways, and although we're already a far more mobile population than Spain apparently is, HSR will still provide economic and environmental benefits that so far we can only imagine.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Open Thread: Next Steps for California?

Last week's announcement of a national strategic plan for HSR was essentially the official start of the intense lobbying efforts by multiple states to secure a slice of the $9.5 billion in federal dollars currently on the table. The plan clarified that "emerging HSR", i.e. selected upgrades from 79mph to 110mph top speed, would be prioritized for phase 1. Related grant awards are supposed to happen by the end of summer, in keeping with the objective of the stimulus bill: turn dirt early.

Last week's announcement of a national strategic plan for HSR was essentially the official start of the intense lobbying efforts by multiple states to secure a slice of the $9.5 billion in federal dollars currently on the table. The plan clarified that "emerging HSR", i.e. selected upgrades from 79mph to 110mph top speed, would be prioritized for phase 1. Related grant awards are supposed to happen by the end of summer, in keeping with the objective of the stimulus bill: turn dirt early.

Strategic corridor development, i.e. "regional HSR" (speeds up to 150mph) and "express HSR" (bullet trains at speeds in excess of 150mph) would be addressed in phase 2. This presumably includes both the Acela, California and Florida corridors. Texas still needs to decide if it wants to split into 5 states so the other 49 will kick them out of the union. Sometime after that, they may get around to deciding on the T-bone network. SoCal-Vegas would also be a bullet train of one type or another, preferably compatible with the California network, but at this point it's not even on the map of federally designated corridors yet.

Congress will have to allocate significant additional funding to make any bullet train system at all feasible in the US. Perhaps the President expects Congress to do just that for him, since his budget proposal includes just $1 billion per year for the next five years for HSR, over and above the $9.5 billion already on the table. He knows full well that's not going to be enough.

So what should the next steps be for California HSR regarding funding? A focus on increasing the regular budget allocation for HSR? A tariff on all crude oil and refined products imported from non-NAFTA contries? A hike in federal or state gasoline tax?

Or should the focus instead shift to making California a center of excellence in HSR technology and associated regulation? Should the state ask FRA to designate a senior liaison who would sit across from a counterpart from the CPUC, with Caltrans Dept. of Rail and CHSRA engineers down the hall in a building in Sacramento? Should there be a formal federal program for developing standards for mobile broadband internet access at speeds of up to 300mph, headquartered in Silicon Valley?

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Obama's HSR Plan (Mostly) Lauded - But How To Pay For It?

Thursday's announcement by President Barack Obama of the HSR Strategic Plan got a lot of attention in the media and on the blogs - which is just what California's project needs at this time. Obama's high-profile leadership for HSR should help focus our state, especially those involved in the contentious debates over how to build the trains along the planned corridor, on the big picture and the need to move forward quickly and effectively in building the high speed trains that are so essential to our nation's future.

Yonah Freemark at The Transport Politic offered this assessment of the plan: